In this dog bladder cancer guide we walk you through the signs you should pay attention to and when you should take your dog to the vet. The most common type of bladder cancer in dogs is transitional cell carcinoma (TCC).

When I was sixteen years old, my family German shepherd, Clancy, gave birth to six puppies on a cold December day. The next morning I leaped out of bed and ran to her whelping area just in time to see a seventh and final puppy come into the world: Bella Marley. I got her for Christmas that year, and she was my first baby. I always said that since I’d been there when she was born, I wanted to be with her when she passed away. When she died of bladder cancer just eight years later, I mourned deeply.

Sixteen-year-old me with week-old Bella Marley.

I say “just” eight years because Clancy lived almost ten. I still keep in touch several of Bella’s littermates, who are now ten themselves and are still healthy and happy. And maybe Bella could still be alive, too, if I’d paid closer attention to her bladder cancer symptoms.

German shepherd Clancy and four of her GSD puppies. Bella is on the right.

But I didn’t know she had bladder cancer until the day before she died.

First Sign of Bladder Cancer in Dogs: Trouble Urinating

Our last happy family camping trip with Bella was to Moab, Utah, two weeks before her death from bladder cancer. She seemed overjoyed to spend time in the open, red-rock desert, and there were no signs of ill health or bladder cancer. If anything, she just seemed tired. We attributed this to the altitude change from sea-level Oklahoma, where we lived at the time.

Me and my babies in Moab, Utah. Our last family trip with Bella.

Once we got home, though, something strange started happening: Bella started spotting blood. She’d never been spayed, so I figured it was her heat cycle coming too soon. My gut told me otherwise—she’d just had a heat cycle two months prior. Most dogs only come into heat once every six months. Bella had followed that schedule her entire life.

I thought her body was confused because she was getting older. In hindsight, I wish I had trusted my instinct and taken her to the vet right away.

By the end of the week, I realized she wasn’t spotting blood, she was straining to urinate. And it wasn’t working. The only thing coming out of her urinary tract were drops of bloody urine.

Emergency Vet Trip

We rushed her to the vet, worried but not petrified. We figured she had a problem—a urinary tract infection, maybe—that antibiotics or a minor surgery could fix. We were willing to fork out hundreds of dollars for whatever Bella needed. She was our first baby, our son’s big sis. She was eight, but she could live three years longer or more. She was worth saving.

Still smiling at the vet because we didn’t know the sorrow the next day would bring.

The vet felt her abdomen and said it was abnormally hard. “It could be an infection,” he said. “We’ll keep her overnight for observation and do x-rays in the morning.”

So we kissed Bella goodnight and told her we’d see her the following day. We hoped that the infection could be gotten rid of easily.

A Terrible Phone Call

The next morning, as I was getting ready to go to work with my eight-month-old son, my phone rang.

It was the veterinarian.

“You’d better come in,” he said. “I’ve done an x-ray and I’m afraid Bella has a very large mass in her bladder and she’s very, very sick. She needs surgery to remove the tumor, but she might not survive it. This might be your last chance to say goodbye.”

I cried all the way to the vet. My husband got the day off work, too, and met me there an hour later.

The vet handed us a box of tissues and took us back to the crate where Bella sat quietly waiting. The blanket beneath her was damp with her bloody urine.

Spending time with our sweet Bella before her bladder cancer surgery.

She politely thumped her tail once but didn’t move to get up. That’s when I finally understood how miserable she was.

We petted her, coaxed her into playing with a tennis ball for a minute or two, and savored the sound of our baby laughing and cooing at her.

We took her outside, knowing it might be her last time to feel sunshine on her face. I took a photo with her. It would turn out to be the last of hundreds.

The last photo Bella and I ever took together.

Then I kissed my baby on the head, told her again how much I loved her, and watched the doctor lead her to the surgery room.

My family headed to the waiting room. For one long hour, we sat and stared and hoped that she’d pull through. At one point, the veterinarian’s assistant came out and told us that she didn’t have a tumor at all! She might live after all.

We got excited, and moments later our hopes were crushed: the vet called us into a little room near the surgery. He said, “I’m sorry, but her bladder is completely dead. The mass was actually urine that had collected for several weeks and been unable to get out through the dead tissue. I believe it’s because of a bladder cancer, but I’ll have to run the tissue under a microscope to know for sure.”

I knew, then, that Bella was dying. “We could put a urinary catheter in to act as a bladder,” the vet said, “but the urinary catheter would only prolong her life for maybe a month, and it would be a month of suffering.”

“I don’t want her to suffer,” I said. “Can I see her?”

I kept remembering the promise I’d made to Bella: that because I’d been there at her birth, I would be with her at her death.

The vet put his hand on my shoulder. “You’re welcome to, but I don’t think you want the way she looks now to be the way you last remember seeing her.”

Bella, just before going into surgery. The last time I ever saw her.

I nodded and edged close to the doorway. Bella was just ten feet away, asleep, and she would never wake up.

“You can let her go,” I said quietly. My husband and I began to cry. But we were both adamant: Bella would not suffer simply to give us another month of her presence.

“It’s a hard choice, but it’s the kind choice.” The vet brought us another box of tissues. “She’ll never know what was going to happen.”

And so I stood by the doorway while the doctor went back to my sweet, reddish-furred German shepherd and eased her peacefully into death. He took a tissue sample from her bladder and confirmed that she had indeed died of bladder cancer.

“It would’ve been really hard to diagnose early,” he said. “She’s probably had it for a couple months.” She’d had her last checkup around six months before. At that time, she’d been healthy.

The vet’s secretary gave us the cremation information, assuring us that the crematory treated dogs with utmost respect. We could even attend Bella’s cremation if we wanted to. We chose not to, but now I wish we had been there to watch over her body’s final moments on this earth.

That night, I sat in the big yard where Bella had loved to chase balls and squirrels. The yard where she played with her baby brother. The yard that was filled with her bloody attempts to urinate.

Happier days: Bella in her big backyard with her baby brother.

And I felt the deepest regret that I hadn’t taken her to the vet right after we got back from Moab and she started “spotting”. She must have suffered intensely that week, and I wish I had taken her to the vet immediately. It probably wouldn’t have changed her prognosis, but it would have ended her suffering sooner.

I’ll always regret that week that I waited.

If your dog shows any signs of bladder cancer (or any other serious disease), such as trouble urinating or blood in the urine, don’t do what I did and wait a week. Take her in right away. You might not be able to save her life, but you’ll at least ease her suffering. If discovered early, the survival time increases.

According to the American Kennel Club, bladder cancer in dogs is rare. There’s only a small chance that your healthy dog will contract bladder cancer. Bella was one of those rare cases with bladder cancer. There are several breeds, however, that suffer from bladder cancer at higher rates than others: Beagles, Shetland Sheepdogs, West Highland white terriers, and Scottish Terriers are among them. The most common type of bladder cancer for dogs with bladder cancer is transitional cell carcinoma (TCC).

I’m grateful for the eight years I had with Bella Marley. I think of her every day still, and she’ll always be such a special dog to our family. Our Alaskan shepherd, Eira, reminds me a lot of Bella—she is half German shepherd, after all. Sometimes I imagine that she and Bella met somewhere in the in-between.

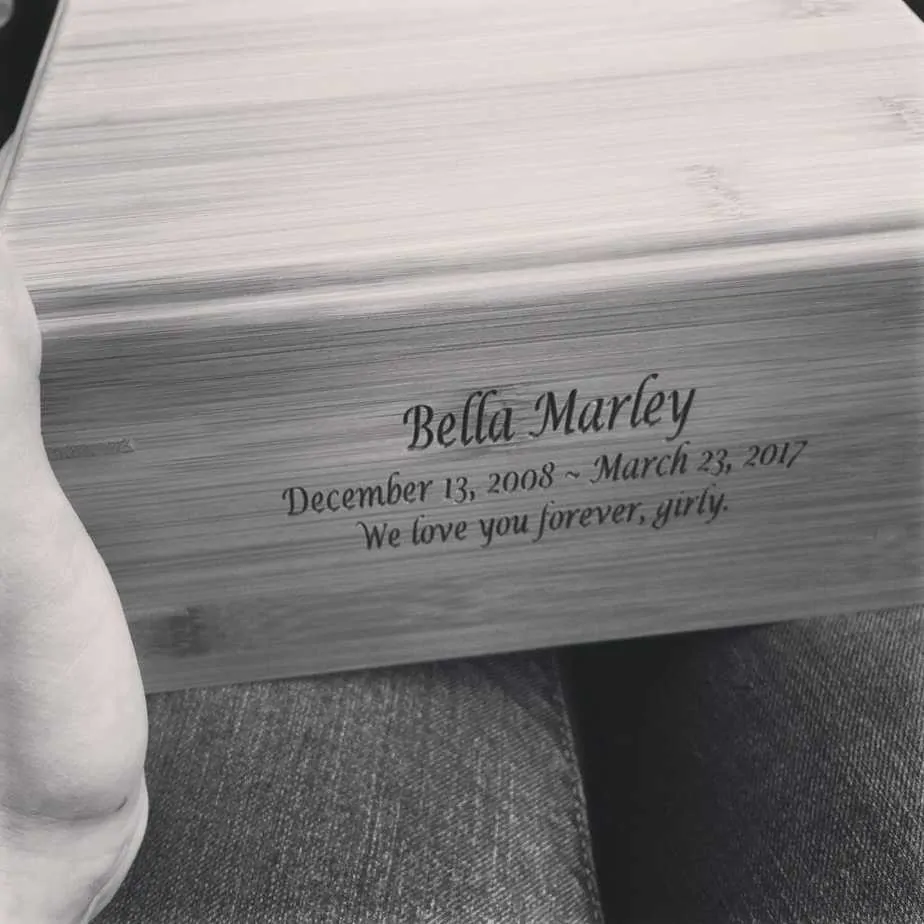

Bella’s bamboo urn containing her ashes.

We’ll always miss our Bella Marley. And I’ll always regret not finding out about her bladder cancer sooner.

Laura Ojeda Melchor grew up with two beloved German shepherd dogs—Clancy and her daughter, Bella. From the time her family brought Clancy home, Laura took on the duty of pooper-scooper and potty trainer. As a teenager Laura helped her mother care for Clancy during her pregnancy. She still remembers fondly the exciting, frigid winter night when the seven special puppies were born. Laura kept the youngest puppy—Bella—and potty trained her, too. She taught Bella important commands, took her for long walks, and spent hours throwing tennis balls for her.

In November, Laura brought home a sweet new puppy, Eira Violet. Eira is half Alaskan malamute and half German shepherd, and Laura loves her deeply. She chose not to use a crate to potty train Eira and was pleasantly surprised at the results. She now has a sweet, energetic dog who always uses the potty outside, plays well with Laura’s toddler, and enjoys long family walks in beautiful Alaska. If you were to meet Eira, she’d bound up to you with a wagging tail and get you running around the yard with her in no time.